Health is Wealth.

Exercise is significant for maintaining a better health

You are unique... improve yourself...

You have gifted talents, discover it...

Health is wealth...

Money can't buy health...

Conquer yourself and mind

There is power within you..discover...

OBESITY and OVERWEIGHT

BMI Calculator

BMI Calculator

What are obesity and overweight

Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health.

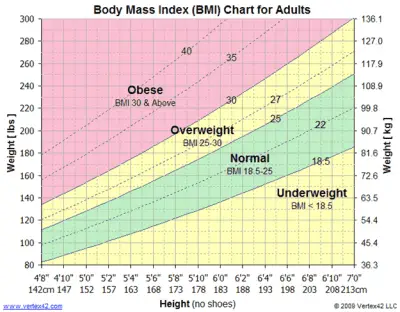

Body mass index (BMI) is a simple index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify overweight and obesity in adults. It is defined as a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of his height in meters (kg/m2).

Adults

For adults, WHO defines overweight and obesity as follows:

- overweight is a BMI greater than or equal to 25; and

- obesity is a BMI greater than or equal to 30.

BMI provides the most useful population-level measure of overweight and obesity as it is the same for both sexes and for all ages of adults. However, it should be considered a rough guide because it may not correspond to the same degree of fatness in different individuals.

For children, age needs to be considered when defining overweight and obesity.

Children under 5 years of age

For children under 5 years of age:

- overweight is weight-for-height greater than 2 standard deviations above WHO Child Growth Standards median; and

- obesity is weight-for-height greater than 3 standard deviations above the WHO Child Growth Standards median.

Children aged between 5–19 years

Overweight and obesity are defined as follows for children aged between 5–19 years:

- overweight is BMI-for-age greater than 1 standard deviation above the WHO Growth Reference median; and

- obesity is greater than 2 standard deviations above the WHO Growth Reference median.

Facts about overweight and obesity

Some recent WHO global estimates follow.

- In 2016, more than 1.9 billion adults aged 18 years and older were overweight. Of these over 650 million adults were obese.

- In 2016, 39% of adults aged 18 years and over (39% of men and 40% of women) were overweight.

- Overall, about 13% of the world’s adult population (11% of men and 15% of women) were obese in 2016.

- The worldwide prevalence of obesity nearly tripled between 1975 and 2016.

In 2019, an estimated 38.2 million children under the age of 5 years were overweight or obese. Once considered a high-income country problem, overweight and obesity are now on the rise in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in urban settings. In Africa, the number of overweight children under 5 has increased by nearly 24% percent since 2000. Almost half of the children under 5 who were overweight or obese in 2019 lived in Asia.

Over 340 million children and adolescents aged 5-19 were overweight or obese in 2016.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents aged 5-19 has risen dramatically from just 4% in 1975 to just over 18% in 2016. The rise has occurred similarly among both boys and girls: in 2016 18% of girls and 19% of boys were overweight.

While just under 1% of children and adolescents aged 5-19 were obese in 1975, more 124 million children and adolescents (6% of girls and 8% of boys) were obese in 2016.

Overweight and obesity are linked to more deaths worldwide than underweight. Globally there are more people who are obese than underweight – this occurs in every region except parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

What causes obesity and overweight?

The fundamental cause of obesity and overweight is an energy imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended. Globally, there has been:

- an increased intake of energy-dense foods that are high in fat and sugars; and

- an increase in physical inactivity due to the increasingly sedentary nature of many forms of work, changing modes of transportation, and increasing urbanization.

Changes in dietary and physical activity patterns are often the result of environmental and societal changes associated with development and lack of supportive policies in sectors such as health, agriculture, transport, urban planning, environment, food processing, distribution, marketing, and education.

What are common health consequences of overweight and obesity?

Raised BMI is a major risk factor for noncommunicable diseases such as:

- cardiovascular diseases (mainly heart disease and stroke), which were the leading cause of death in 2012;

- diabetes;

- musculoskeletal disorders (especially osteoarthritis – a highly disabling degenerative disease of the joints);

- some cancers (including endometrial, breast, ovarian, prostate, liver, gallbladder, kidney, and colon).

The risk for these noncommunicable diseases increases, with increases in BMI.

Childhood obesity is associated with a higher chance of obesity, premature death and disability in adulthood. But in addition to increased future risks, obese children experience breathing difficulties, increased risk of fractures, hypertension, early markers of cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance and psychological effects.

Facing a double burden of malnutrition

Many low- and middle-income countries are now facing a “double burden” of malnutrition.

- While these countries continue to deal with the problems of infectious diseases and undernutrition, they are also experiencing a rapid upsurge in noncommunicable disease risk factors such as obesity and overweight, particularly in urban settings.

- It is not uncommon to find undernutrition and obesity co-existing within the same country, the same community and the same household.

Children in low- and middle-income countries are more vulnerable to inadequate pre-natal, infant, and young child nutrition. At the same time, these children are exposed to high-fat, high-sugar, high-salt, energy-dense, and micronutrient-poor foods, which tend to be lower in cost but also lower in nutrient quality. These dietary patterns, in conjunction with lower levels of physical activity, result in sharp increases in childhood obesity while undernutrition issues remain unsolved.

How can overweight and obesity be reduced?

Overweight and obesity, as well as their related noncommunicable diseases, are largely preventable. Supportive environments and communities are fundamental in shaping people’s choices, by making the choice of healthier foods and regular physical activity the easiest choice (the choice that is the most accessible, available and affordable), and therefore preventing overweight and obesity.

At the individual level, people can:

- limit energy intake from total fats and sugars;

- increase consumption of fruit and vegetables, as well as legumes, whole grains and nuts; and

- engage in regular physical activity (60 minutes a day for children and 150 minutes spread through the week for adults).

Individual responsibility can only have its full effect where people have access to a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, at the societal level it is important to support individuals in following the recommendations above, through sustained implementation of evidence based and population based policies that make regular physical activity and healthier dietary choices available, affordable and easily accessible to everyone, particularly to the poorest individuals. An example of such a policy is a tax on sugar sweetened beverages.

The food industry can play a significant role in promoting healthy diets by:

- reducing the fat, sugar and salt content of processed foods;

- ensuring that healthy and nutritious choices are available and affordable to all consumers;

- restricting marketing of foods high in sugars, salt and fats, especially those foods aimed at children and teenagers; and

- ensuring the availability of healthy food choices and supporting regular physical activity practice in the workplace.

WHO response

Adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2004 and recognized again in a 2011 political declaration on noncommunicable disease (NCDs), the “WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health” describes the actions needed to support healthy diets and regular physical activity. The Strategy calls upon all stakeholders to take action at global, regional and local levels to improve diets and physical activity patterns at the population level.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognizes NCDs as a major challenge for sustainable development. As part of the Agenda, Heads of State and Government committed to develop ambitious national responses, by 2030, to reduce by one-third premature mortality from NCDs through prevention and treatment (SDG target 3.4).

The “Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world” provides effective and feasible policy actions to increase physical activity globally. WHO published ACTIVE a technical package to assist countries in planning and delivery of their responses. New WHO guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep in children under five years of age were launched in 2019.

The World Health Assembly welcomed the report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity (2016) and its 6 recommendations to address the obesogenic environment and critical periods in the life course to tackle childhood obesity. The implementation plan to guide countries in taking action to implement the recommendations of the Commission was welcomed by the World Health Assembly in 2017.

SOURCE: Obesity and overweight (who.int)

[BMIAKC_adult_calc lang="English" id_calc="e1707419405" units="metric" ]

Factors affecting the accuracy of BMI

How accurate is BMI?

File this one under “it’s complicated.” As your BMI rises, your risk for health problems increases as well. For example, people who have BMIs in the overweight or obesity ranges are at higher risk for developing diabetes than people in the normal range.

“That risk may be twice as high,” says Dr. Heinberg. “But when you look at people whose BMIs are more than 40, the risk may increase to 20 times higher.”

BMI is an exercise in health probability. Does a high BMI mean you automatically have poor health? No. Does it dramatically increase your risk of poor health? Absolutely.

For example, not everyone who has a BMI over 40 has diabetes. But many more people with BMIs over 40 have diabetes than people in the overweight or normal weight range.

“A too-high or too-low BMI is not an ironclad guarantee that you will develop a chronic disease,” notes Dr. Heinberg. “Rather, it’s an important piece of information that you and your primary healthcare provider should look at within the context of evaluating you as a whole person.”

Why isn’t BMI accurate in some cases?

Some exceptions can make BMI seem more like a Magic 8 Ball, though. Factors that can make BMI not accurate include:

Race and ethnicity

When it comes to BMI, all races and ethnicities are lumped together — and that can lead to unclear and confusing results. More and more research shows that there are biological and genetic differences in the relationship between weight, muscle mass and disease risk among different groups of people. BMI does not account for that.

Certain genetic factors can affect BMI accuracy because of their effect on weight distribution and muscle mass. For example, a 2011 study showed that Black women had less metabolic risk at higher BMIs than white women. Another showed that Mexican American women tend to have more body fat than white and Black women.

Other research shows that for people of Asian or Middle Eastern descent, even a lower BMI may be misleading. They have a higher risk for metabolic diseases like diabetes at a lower BMI than people of European descent.

“The cutoffs we use may miss some people who are high risk and may need earlier intervention,” Dr. Heinberg notes. “They might not get the preventive care they need since they look at their lower BMI and think, ‘Great, I’m in good health, I don’t need to do anything’.”

Muscle mass

People who are athletic tend to have a higher percentage of lean muscle mass and a lower percentage of fat mass than the average population. These factors can throw a wrench in their BMI measurements. They might measure in the overweight category (or higher) despite having great overall health.

Weight distribution

Being pear- or apple-shaped doesn’t just affect clothing preferences. “BMI does not take waist circumference into account,” explains Dr. Heinberg. “Two people can weigh the same and, therefore, have the same BMI. But their risk for disease might not be the same.

“Say Person A has a higher waist circumference, carrying their weight in their abdomen. Person B carries their weight lower in their body. Person A has a higher risk of metabolic and cardiovascular disease, but their identical BMI doesn’t tell that story,” she notes.

Age

Older adults tend to have more body fat and less muscle mass — but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Studies show that BMIs in the high-normal to overweight range may protect older adults from developing certain diseases and dying early.

Does your BMI still matter?

Think of BMI like a puzzle piece: It’s a part of your whole health picture. Other valuable pieces include:

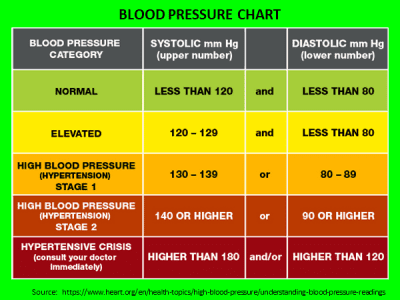

- Blood pressure: Blood pressure measures the pressure of your blood against your artery walls as your heart beats. It’s a good indicator of heart health and heart disease risk.

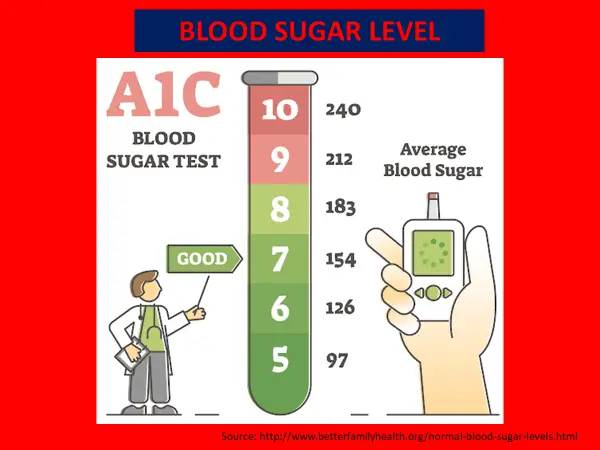

- Blood sugar: Blood sugar tests tell you how much glucose (sugar) is in your blood. They help doctors screen for pre-diabetes and diabetes.

- Cholesterol: Your cholesterol levels show the amount of LDL (bad) and HDL (good) cholesterol in your blood. Too much LDL increases your heart attack and stroke risk.

- Heart rate: A high resting heart rate puts you at increased risk for heart attack and death.

- Inflammation: Chronic inflammation is linked to diseases like cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, heart disease and Type 2 diabetes.

- Lean muscle mass versus fat mass: A higher percentage of lean muscle mass can protect against obesity and obesity-related conditions, including diabetes.

- Waist circumference: You have a higher risk for developing obesity-related conditions if your waist circumference is more than 40 inches (men) or more than 35 inches (nonpregnant people).

“Knowing a patient’s lean muscle mass versus fat mass may be more informative than BMI, but it’s hard to measure accurately and cheaply,” adds Dr. Heinberg. “Waist circumference is also hard to measure accurately, particularly in patients with greater obesity.

“That’s one of the reasons we rely on BMI. All you need is a scale, stadiometer (which measures height) and calculator,” she says.

Dr. Heinberg’s take-home point: Even with its many exceptions, don’t throw the BMI baby out with the bathwater.

“Blood pressure tells you about cardiovascular risk, but BMI tells you about risk for that and other conditions like cancer, endocrine disorders and sleep apnea,” says Dr. Heinberg. “Knowing someone has obesity based on BMI can lead to a more comprehensive evaluation with their doctor.”

SOURCE: Is BMI an Accurate Measure of Health? – Cleveland Clinic

Eat healthy, dietary foods in moderation

Dancing with groups makes you alive and happy...

Walking is the best exercise

CARDIO & STRENGTH TRAINING

BMI Chart

| NORMAL WEIGHT | OVERWEIGHT | OBESE | |||||||||||||||

| BMI Value: | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 |

| Height cms (meters) | Body Weight (kilograms / kg) | ||||||||||||||||

| 147cm (1.47m) | 41 | 44 | 45 | 48 | 50 | 52 | 54 | 56 | 59 | 61 | 63 | 65 | 67 | 69 | 72 | 73 | 76 |

| 150cm (1.50m) | 43 | 45 | 47 | 49 | 52 | 54 | 56 | 58 | 60 | 63 | 65 | 67 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 76 | 78 |

| 152cm (1.52m) | 44 | 46 | 49 | 51 | 54 | 56 | 58 | 60 | 63 | 65 | 67 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 76 | 79 | 81 |

| 155cm (1.55m) | 45 | 48 | 50 | 53 | 55 | 57 | 60 | 62 | 65 | 67 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 79 | 82 | 84 |

| 157cm (1.57m) | 47 | 49 | 52 | 54 | 57 | 59 | 62 | 64 | 67 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 79 | 82 | 84 | 87 |

| 160cm (1.60m) | 49 | 51 | 54 | 56 | 59 | 61 | 64 | 66 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 79 | 82 | 84 | 87 | 89 |

| 163cm (1.63m) | 50 | 53 | 55 | 58 | 61 | 64 | 66 | 68 | 71 | 74 | 77 | 79 | 82 | 84 | 87 | 89 | 93 |

| 165cm (1.65m) | 52 | 54 | 57 | 60 | 63 | 65 | 68 | 71 | 73 | 76 | 79 | 82 | 84 | 87 | 90 | 93 | 95 |

| 168cm (1.68m) | 54 | 56 | 59 | 62 | 64 | 67 | 70 | 73 | 76 | 78 | 81 | 84 | 87 | 90 | 93 | 95 | 98 |

| 170cm (1.70m) | 55 | 57 | 61 | 64 | 66 | 69 | 72 | 75 | 78 | 81 | 84 | 87 | 90 | 93 | 96 | 98 | 101 |

| 172cm (1.72m) | 57 | 59 | 63 | 65 | 68 | 72 | 74 | 78 | 80 | 83 | 86 | 89 | 92 | 95 | 98 | 101 | 104 |

| 175cm (1.75m) | 58 | 61 | 64 | 68 | 70 | 73 | 77 | 80 | 83 | 86 | 89 | 92 | 95 | 98 | 101 | 104 | 107 |

| 178cm (1.78m) | 60 | 63 | 66 | 69 | 73 | 76 | 79 | 82 | 85 | 88 | 92 | 95 | 98 | 101 | 104 | 107 | 110 |

| 180cm (1.80m) | 62 | 65 | 68 | 71 | 75 | 78 | 81 | 84 | 88 | 91 | 94 | 98 | 101 | 104 | 107 | 110 | 113 |

| 183cm (1.83m) | 64 | 67 | 70 | 73 | 77 | 80 | 83 | 87 | 90 | 93 | 97 | 100 | 103 | 107 | 110 | 113 | 117 |

| 185cm (1.85m) | 65 | 68 | 72 | 75 | 79 | 83 | 86 | 89 | 93 | 96 | 99 | 103 | 107 | 110 | 113 | 117 | 120 |

| 188cm (1.88m) | 67 | 70 | 74 | 78 | 81 | 84 | 88 | 92 | 95 | 99 | 102 | 106 | 109 | 113 | 116 | 120 | 123 |

| 191cm (1.91m) | 69 | 73 | 76 | 80 | 83 | 87 | 91 | 94 | 98 | 102 | 105 | 109 | 112 | 116 | 120 | 123 | 127 |

| 193cm (1.93m) | 71 | 74 | 78 | 82 | 86 | 89 | 93 | 97 | 100 | 104 | 108 | 112 | 115 | 119 | 123 | 127 | 130 |

| Height cms (meters) | Body Weight (kilograms / kg) | ||||||||||||||||

| BMI Value: | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 |

| NORMAL WEIGHT | OVERWEIGHT | OBESE | |||||||||||||||

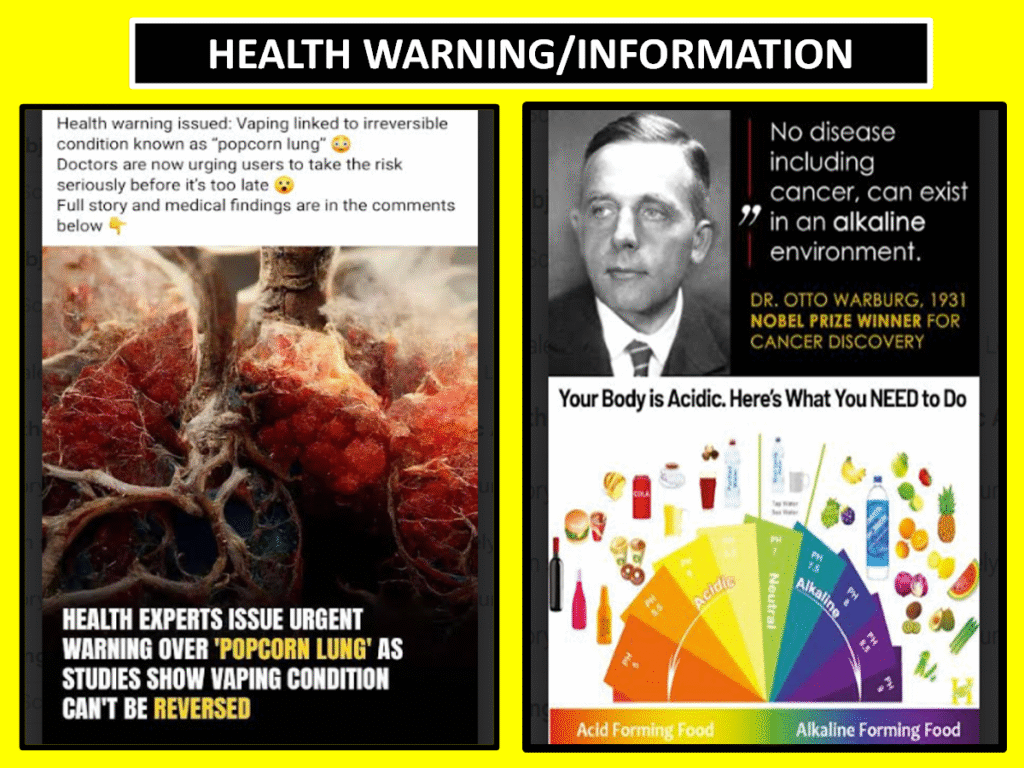

CHECK YOUR BLOOD SUGAR REGULARLY

NO TO SELF-MEDICATION